Sir Walter Scott saves the Scottish Parliament - well, bits of it...

- Robert Sproul-Cran

- Feb 25

- 5 min read

Last time we found some promising pieces of masonry - but to see more we might need to head into Abbotsford and lift our eyes heavenwards!

When Sir Walter Scott poured his earnings from the massively successful Waverley Novels into his new house at Abbotsford, near Galashiels in the Scottish Borders, he was wealthy enough to indulge his passion for romanticising Scottish history. As you can see from the photo above he borrowed architectural features from castles, towers, churches - and his own fertile imagination! Look at the right hand tower, with battlements around the top. Did he expect he'd have to use archers to defend his new house? To the left of this we have crow-step gables - a typically Scottish feature. But the chimneys behind might be more at home on a Tudor mansion in the south of England. But despite this odd mixture of styles the overall effect is quite charming, and inspired imitators to develop what became know as 'Scottish baronial' architecture.

But that's not the point of our search. Not only did he borrow stylistic features - he also laid his hands on interesting chunks of original buildings, and had the masons build them into his new home. Look at the crosses on two of the gables, or the crest above the entrance. These came from earlier buildings, and Scott - an avid and wealthy collector - incorporated them into his grand new home.

Now cast your eyes up and to the left of the main door.

There's a door built into the wall. This is an odd place to find a massive wooden door. In fact it doesn't lead anywhere. It doesn't open. It just sits there, barely noticed by visitors in the courtyard below. Let's take a closer look, from an upper floor.

This is the door from Edinburgh's Old Tolbooth. Tolbooths were sites of city administration in early Scotland, large public buildings or townhouses that did much of what modern councils now carry out. The Scottish Parliament would be based in the Tolbooth when it was sitting in Edinburgh, and the top civil court of Scotland, the Court of Session, would also make use of the Tolbooth for its hearings. The city magistrates and staff used the building, and on occasion it was also used by the functionaries of St Giles. In addition, it soon developed a further function, as the city prison, which became its sole use after 1563.

That prison was notorious as a site of torture and public executions. To this day it's still common to see the people of Edinburgh spit on the 'Heart of Midlothian' - the cobble pattern in the pavement which marks where the Tolbooth used to stand. It's believed that Scott didn't make use of the door as a functioning piece of architectural salvage since so many folk made their last journey through it over the centuries. But he still quite fancied it on his wall to make the place look interesting!

We'll return to the Tolbooth in future blog posts, but for the moment we're just interested in this door. We can cross-reference its authenticity by referring to a watercolour by James Skene, painted a few years after the building was demolished in 1817.

The studded wooden door is unmistakably from the Old Tolbooth. But the stone surround has no inscriptions, and the ornate pediment is missing. And yet it looks strangely familiar. Let's break off for a minute and charge back out into the woods. There, just a few yards from Abbotsford House, lies a pile of masonry.

And on the left hand side is an unmistakable shape. It is curved, in order to fit onto a tower rather than a flat wall. It is the lintel painted by Skene.

In the course of this investigation the Abbotsford Trust had experts in to clean up the stones. And the results are wonderful...

The embellishments above the ogee arch are shown to be thistles, and the fine carving above the door is now revealed in its original detail. It is surely no coincidence that the other stones are laid out in a circle. So if the inscribed door surround on the wall at Abbotsford doesn't come from the Tolbooth, do we have the correct door jambs here in the woods? It's no surprise that some of the stones in the circle might fit the bill.

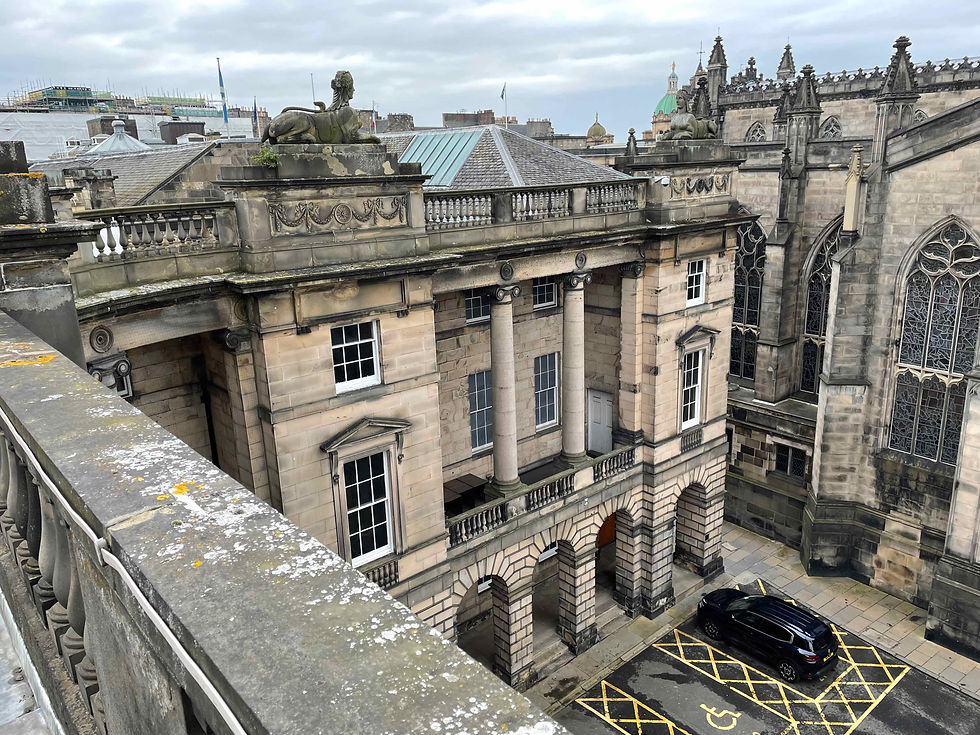

We're getting carried away here on a new quest, one which we'll return to before long. But today we're still on the hunt for parts of the old Scottish Parliament, and in particular the triangular pediments from above the ground floor windows.

So back to the Tolbooth door on the Abbotsford wall. Yes, I know you spotted that straight away, but I was heading down the Tolbooth rabbit hole. What is that above the door where the Tolbooth lintel ought to be?

Yes, it's a triangular pediment, with the word ANNO carved on it. It has a thistle and a rose. And it has that distinctive change of angle where the cornice meets the base. So why would you have just the word 'anno', or 'year', on a pediment? It would only makes sense if there was a date somewhere next to it. A date like '1636' on the pediment which still sits in Parliament Square.

It looks as if we might have the left and right downstairs pediments from the main facade of the old Scottish Parliament. As we discovered last time there is a third by the Tolbooth masonry circle in the woods. So is there a fourth? The answer sits above a garden gate on the north side of the building, hidden away, and partly covered by ivy.

Again it has a thistle and a rose, with a crown in the centre, and the initials CRI to either side of a lion rampant - denoting King Charles I. It has the change of angle at the base of the cornice. And as a bonus, there are two more of the pyramid stones which originally featured on either side of the main Parliament door. We saw more of these at Arniston House near Peebles.

Let's take a look at all four together to see if we have a set. The ANNO 1636 pair seem quite compelling. The 1636 one in Edinburgh has a carving of a metal loop and ring to either side of the crown, to which are tied bunches of grapes. The pediment above the Abbotsford garden gate has the same device, this time with ribbons attached. Their size, proportions and architectural style seem an excellent match.

But one puzzle is that the style of carving is quite different, with some much bolder than others, as if they were carved by different masons. The answer might be that they were carved by different masons!

So what do you think? Have we found the set of four pediments, from Parliament Hall and the adjacent 'jamb'? Check the 17th and 18th Century prints of the scene in previous blog posts and let me know what you think in the comments below.

The problem I see is that the pediments on the east face of the Parliament Buiding as shown in the prints seem to be undecorated. You can see the ones on the north face are decorated even though these are in shadow. Doesn’t mean the ones you’ve found aren’t and I think there is a good case stylistically that they are but, in this case, the contemporary prints are your enemy rather than your friend